Douglas Schmidt

Previous articles have addressed mergers & acquisitions in a recession as well as the relationship between strategic buyers and private equity buyers.

This article speaks to companies who are thinking about or in the process of raising funds from venture capital providers. It describes traditional venture capital investing in early stage companies. If you are such a company, it may be a rough road ahead. Here is why.

Luck and the Venture Capitalist

To be a successful venture capitalist, you need three traits. First, you need to have an objective, research-focused mentality. Second, you need to be a good judge of character and leadership. Third, you need luck. You need to be fortunate because thousands of others share with you the first two traits.

Luck, or the odds of winning, is not a meaningless contributor to venture capital success. Consider some simple math. A venture partner makes on average one or maybe two investments each year. Let’s say that the life of her fund from which she draws her investment capital requires her to post some results within five years. So, at most, and I mean at most, she has invested in 10 companies in five years. But, unlike private equity or LBO funds which invest in on-going concerns with real sales, these venture investments are all risky start-ups or early stage companies. Many of them do not survive the life of the fund.

An old rule of thumb used to be that three or four investments will flat-out fail. Three or four will return her investment with little to no gain. That leaves two or three that will make money. Somewhere in those two or three,among the handful of investments left standing after five years,is supposed to be the home run.The homerun is the one deal that makes up for all her failed companies and gets her quoted in the press as the next tech guru.

Why do I seem to speak with authority on this topic? Because many years ago, I took a break from my investment banking career to be a partner for two years in a venture firm just as the Dotcom Bubble burst and plunged us into the recession of 2001. I have what we used to call on Wall Street “scar tissue.”

Not only was it the worst of times for investing, I was horrible at being a venture capitalist. I did not have enough of that first criterion of a dispassionate, research-focused mentality that makes VC personalities so beloved around the world. I am “deal guy”; I think all my clients are the greatest companies in the world. That’s a disastrous trait for a venture capitalist who is searching through hundreds of companies for that winning investment and must say no to entrepreneurs with almost every breath.But for the purposes of this article, my experience serves to look at recessions and venture capital from a unique perspective.

Time and Uncertainty

Time is the enemy of the entrepreneur and the friend of the venture capitalist. For the entrepreneur, every unfunded day that slips by is a day not moving toward success and taking money out of his personal pocket or his families’ and friends’ pockets. For a venture capitalist, every additional day before investing allows her to get closer to the entrepreneur and watch the company’s progress. For the entrepreneur, it seems like the VC is toying with his company and success. For the VC, she has to be certain that the risk of failure is manageable and that company milestones (like completion of code or a first customer) get achieved. There can be no rushing into a new investment just because the entrepreneur was ready yesterday for the funds.

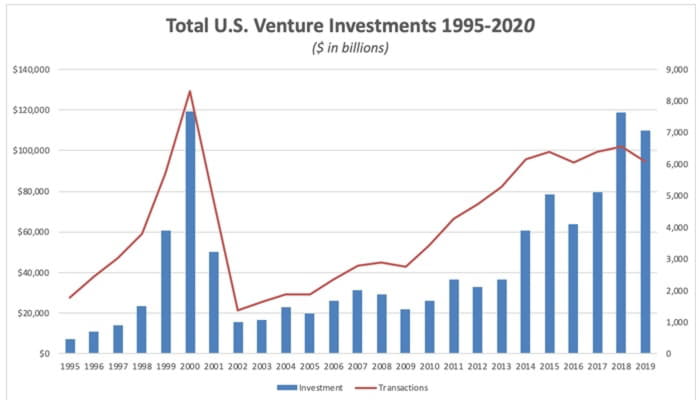

The passage of time leads to why recessions dampen venture investing more than they do private equity investing. The chart below shows clearly how venture investing fell precipitously in 2001 and 2002 after the collapse of the Dotcom Bubble. There were other factors at play, but the recession was the trigger. Likewise, you can see a decline after the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. That was followed by the tremendous built-up of venture investing that by the end of 2019 has rivaled the Dotcom build-up. We await the statistics on what will be a fall-off of venture investment post COVID-19.

Source: PwC/CB Insights MoneyTree™ Report

A recession destroys venture capital investment far more than it does private equity investment. In a recession, customers, whether companies or individuals, quit or reduce buying. Overnight, executives and boards of directors put major expenditures on hold, especially new ones. Private equity investments, by definition, are made into existing companies. Those companies have established sales and customers. In a recession, most of these companies will be in industries that see a drop-off in revenue, but they still have a base of business. Some companies and industries (such as cybersecurity or cloud) will hold their own or even see an increase in business.

But not true with venture companies. There are few to no existing customers. That first big sale and customer is just around the corner. Most venture companies require customers to put precious dollars into a new idea. For a hot new concept, recessions are like a blanket thrown over a fire.

G&A or Old-Fashioned Accounting

Venture capitalists hate with a passion investing in G&A (general and administrative expenses), otherwise known as overhead.They want their money to go directly toward new products, new software, producing salespeople---things that create sales and revenue.Dollars spent keeping a company afloat while waiting for the market to return are lost, unproductive dollars. Even in a boom economy, venture capitalists are judging an investment by how productive their dollars will be. In a recession, venture capitalists fear becoming the parent of teenagers who keep digging into the wallet on Friday night.

In a recession, entrepreneurs are coming to venture capital in desperate need to keep their doors open and accomplish their strategic plan. They are presenting future sales and milestones that a recession throws into uncertainty. Who knows when the economy will regain its strength? Who knows when buyers will stop putting you off and finally ink that contract on your new product or service?

The venture capitalist is faced with funding the operations and overhead of a new investment for an indeterminant amount of time before the investment produces results. Capital designated for growth goes into salaries and rent while the economy is on hold. All capital is fungible. Even for a private equity investment, investment dollars may shift more to G&A and maintenance and away from growth line items. But the difference is clear. A private equity investment should be a fully functioning company with some offsetting revenue. A venture investment may have little to no revenue.

It is an untenable choice for a venture capitalist. They become the bank of first and last resort in a recession. So, they wait and wait to make that investment. They wait for a sign that the market will deliver. This waiting will most assuredly translate into decreased numbers of investments and investment dollars when the post-COVID-19 statistics are reported.

The Personal Touch

A second reason for a downturn in venture investing in the coronavirus recession is one that was unimaginable before this year. As I listen to venture capitalists describe their current work, I am reminded of the second criterion: venture capitalists need to be a good judges of character.

In venture capital, the entrepreneur and leadership team get the largest weighting for success. Venture partners give entrepreneurs unsecured money to grow an untested product or service. The venture capitalist is wholly dependent upon the entrepreneur delivering on his vision and promises. There has to be the highest level of trust between the two, which when successful, has created some famous and wealthy partnerships such as Accel Partners and Facebook, Softbank and Jack Ma’s Alibaba, Sequoia Capital and WhatsApp, and many more.

Here is the unique coronavirus dilemma. How do you create that trust when you can’t meet the entrepreneur face-to-face over multiple meetings and dinners? How do you create that trust when you don’t dare get on an airplane to the next city and risk bringing the virus home to your family? Do not underestimate the human factor in the venture capital decision. Whole careers are made through this trust between investor and entrepreneur. And whole careers are ruined when it goes wrong. Venture capital investments are being “pushed to the right” by economic factors for sure—but also by this personal one unique to 2020.

Overhang and Hope

The chart below shows a massive increase in venture investing over the last bull market since the Great Recession. Just as we showed with private equity investing, the chart depicts the significant amount of undeployed money committed to venture funds and accumulated through the end of the third quarter of 2019. These undeployed funds are otherwise known as the “overhang.”

Global Venture Capital Overhang ($ in billions)

Source: PitchBook | Geography: Global *As of September 30, 2019

The overhang is the greatest hope for entrepreneurs seeking venture capital. If the overhang remains solid, meaning that it is not diverted to current portfolio companies or is not yanked by the limited partners who supply venture funds with money, then there will be intense competitive pressure for venture capitalists to return to the market and invest. If you couple that with the fact that the economy was in very good shape before COVID-19 hit like a meteor from the sky, then there is hope that venture capital investing will bounce back quickly. But make no mistake, if past recessions apply to this one, venture capitalists will hold onto their cards tightly and wait for a clear upward trend in the economy.

Recessions are a tough time to be raising new capital. Most entrepreneurs seeking venture capital will just have to wait it out. Or, they should be realistic about their chances of raising traditional venture capital and consider alternative sources including doubling down with existing investors, family offices, super angels or even crowdsourcing.

Doug Schmidt has been an investment banker for over 35 years, specializing in small and middle market merger & acquisition transactions as well as raising capital for growth companies. His previous firms include Drexel Burnham Lambert and Legg Mason Wood Walker before founding Chessiecap, Inc.in 2004.