Douglas Schmidt

(Second in a series on corporate finance during an economic crisis.)

We know from the history of recessions that thousands of mergers and acquisition (M&A) transactions occur each year, even in an economic downturn. In this strange coronavirus recession, who is going to buy your business and how much will they pay?

Strategic Versus Financial Buyer

For most of the forty years since the creation of the modern LBO in the early 1980s, Strategic buyers have paid more for target companies than financial buyers. Strategic buyers are mature corporations, often pioneers and leaders in their fields.They have established products and services that can swell cash on the balance sheet. Cisco Systems and Oracle acquired scores of acquisitions in the late 1990s and were key drivers of the Tech Boom, often cashing out private equity and venture funds.

Strategic buyers not only had cash, they had the advantage of adding a target’s business to their own business, thus creating “synergies.” Synergies are a rationale used by all buyers to pay more for a company than the financial numbers would dictate.

[I once knew a chief financial officer who distained the term “synergies.” “One plus one never equals three,” he used to say. Whether synergies are real or magical thinking is a topic for another day. The point is that if a buyer is willing to pay for synergies, a seller is happy to accept the largesse.]

The original Financial buyers were Leverage Buyout(LBO) funds, which were radically different creatures than they are today. LBOs were developed in an era of expensive debt and were constrained by their very name“leverage,”which means debt or bank financing.The traditional LBO fund brought a mix of its own equity to the table as well as cash obtained from debt financing. They rose to power in the 1980s with the help of firms like Drexel Burnham Lambert and were epitomized by names such as KKR, Clayton Dubilier & Rice, and Welsh Carson. Today, the term “Private Equity” or “PE fund” is used as a full substitute for LBO firms. “Private Equity” has a kinder, gentler ring to it.

Because of leverage, there was a calculable limit to what an LBO firm could pay for a business. In a fair fight, if the Strategic buyer really wanted the target company, the Strategic buyer could stretch the pricing,and the Financial buyer would always lose. Often,Financial buyers would refuse to be part of an auction in which they thought a Strategic buyer would be bidding. It was a guaranteed defeat and waste of time.In the Old WorldOrder, Financial buyers provided the pricing floor for the market. Strategic buyers were the sought-after ceiling.

The Rise of Private Equity

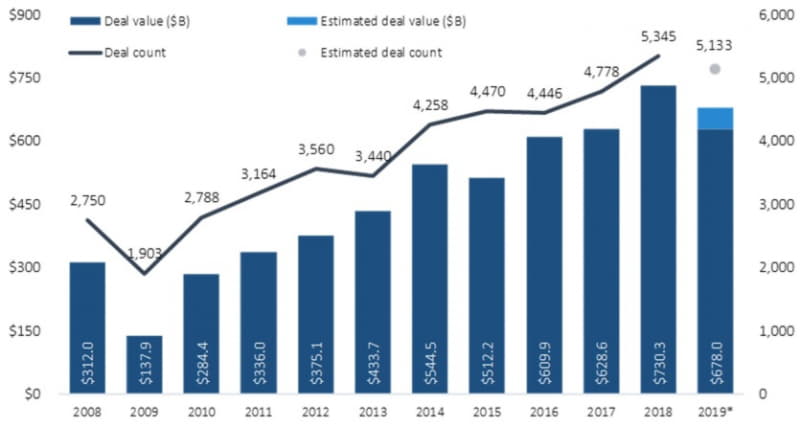

In the last decade since the Great Recession of 2008, the growth of money going into Private Equity funds has been phenomenal. In the chart below, you see the steady rise of deals completed since 2008, totaling over $800 billion or almost 4 times the low in 2009. Alongside this growth in capital invested has been a sustained period of historically low interest rates. Low interest rates reduce the cost of debt and allow the PE firms to pay higher prices.

With so much money parked in Private Equity and fueled by low interest rates, the old rules have gone out the window. The line between strategic and financial buyers is no longer a bright one. The rise of Private Equity has created Financial firms that can act like Strategic buyers. A handful of them including Blackstone (NYSE:BX), Apollo (NYSE:APO), Carlyle (NYSE:CG) and KKR (NYSE: KKR) are now major publicly traded companies. Financial buyers routinely compete with and outbid Strategic buyers.

US PE Deal Activity 2008-2019

Source: PitchBook Data, Inc.

Too much money, too many PE funds, and not enough deals. This translates into competition and competition translates into higher and higher multiples paid for companies. In recent years, PE professionals have railed against the multiples they have had to pay to win businesses. Dog-eat-dog. One PE fund would outbid the next, with no one to blame but themselves.

In its “Global Private Equity Report 2020,” Bain & Company reports for 2019 that “More than 55% of US buyout deals had a multiple above 11x.” This means a purchase price that was an astounding 11 times EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization—or cash flow). Even for small transactions, PE buyers have complained bitterly about having to pay up to 9 times (9X) EBITDA or more in order to win a deal.

In the early years of the LBO, if you paid 5 times (5X) EBITDA, you were at the high end of the range. An 11X multiple means that if a purchased company does not grow, an investor will have to wait 11 years (assuming no taxes) just to get its money back. This is la-la land pricing. It puts tremendous pressure on purchased companies to immediately grow revenues and profits—and certainly not to run into a recession.

The Covid-19 Crash

As soon as the stock market crashed in February of 2020, we heard the rumblings of repricing of deals and a general sigh of relief throughout the world of Private Equity. Multiples paid for businesses would have to come down to rational levels. Pricing power would shift from the seller to the PE buyer.

A reset or reduction of multiples paid is normal and expected in a recession. A recession cures economic imbalances, brings down over-valued sectors, and generally levels the playing field. But with this COVID-19 recession, something is very different.This recession hit like an asteroid in the middle of a picnic. We were experiencing one of the longest economic expansions in history. Most sectors of the economy were doing just fine. None seemed to be overheated. Unemployment was low. Growth was steady.When COVID-19 hit, it did not feel like we had earned a traditional recession.

Recessions have typically culled the herd of Private Equity firms, punishing the foolish and laying waste to poorly constructed leveraged transactions.Those firms with portfolios full of over-priced deals in struggling industries fall by the wayside. With fewer PE firms, competition is reduced. Multiples paid come down. Again, supply and demand rule.

The biggest unknown in this coronavirus recession is how much damage will be done to PE firms and their thousands of portfolio companies. As I write this, associates and analysts in PE firms around the world are burning the midnight oil trying to determine if their firms’ portfolio companies can make it through mitigation to a re-start of the economy. Portfolios full of restaurants and retailers are obviously under pressure.But since most portfolio companies and most sectors of the economy were healthy before the asteroid hit, no one knows yet what the effect will be on competition and pricing.

The Illusive Overhang

On paper, there remains an immense amount of money committed to Private Equity. Some funds, particularly ones that have just raised money, are advertising that they are open for business and ready to invest. Is this just bravado, and will these funds still pay high multiples when the deals finally close?

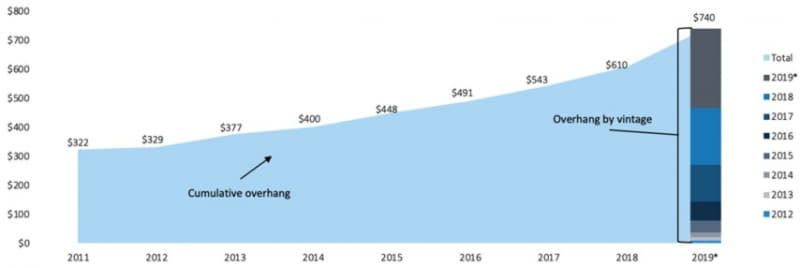

In the chart below, you can see what is called the capital “overhang,” the amount of money that was committed to Private Equity but was not yet invested as of last year.(Also called “dry powder.”) At mid-year 2019, this overhang was a whopping, estimated $740 billion. The yearly increase in multiples paid for businesses tracks this yearly increase in the overhang.

Source: PitchBook Data, Inc.

The big unanswered question that ultimately affects pricing is: “In this recession, how much damage will be done to the overhang?” The overhang can shrink quickly for many reasons, including balky investors. But the main and obvious reason is if PE funds are forced to divert excess cash into struggling portfolio companies.

The Likely Future

The big change coming out of a recession will be the initial dependence of sellers on Strategic buyers. In the early months, advantage should return, for the first time in many years, to corporate acquirers.

Strategic buyers will continue to have reasons to add products and services in order to grow. In many growth industries such as software, cloud, edtech, health care, security, green, and biotech, the multiples paid may remain high. Strategic buyers in industries that have weathered the COVID-19 storm well (such as many tech sectors) will have plenty of cash and can still justify prices based on need or synergies.

Our prediction is that many Financial buyers will be hesitant to act.Many will be preoccupied with steading their own portfolios. Many will look cautiously on target projections in a slowed down economy. And many will be looking for that hoped for break in the market, taking the measure of the market for lower multiples.

If the recession is short and if Private Equity portfolios of companies do not suffer major losses and if debt remains available and low-cost, then the same dynamic of too much money chasing too few deals will still be operative. It may prove impossible for Private Equity to hold to any new low pricing discipline. Multiples paid for businesses can creep quickly back to pre-recession levels, and PE firms will be back competing toe-to-toe with Strategic buyers.

Coming out of this coronavirus recession, low-growth, low-profitability businesses in everyday industries like distribution or manufacturing will suffer the most. If you are a seller of such a business, there is no sugarcoating how difficult it may be to find a good buyer at a price that interests you.But our original observation may bring you some comfort. Thousands of transactions occur each and every year, regardless of the health of the underlying economy. Yours could be one of them.

Doug Schmidt has been an investment banker for over 35 years, specializing in small and middle market merger & acquisition transactions as well as raising capital for growth companies. His previous firms include Drexel Burnham Lambert and Legg Mason Wood Walker before founding Chessiecap. Inc.in 2004.