Douglas Schmidt

(First in a series on corporate finance during an economic crisis.)

Never Catch a Falling Knife

With the stock market experiencing extreme volatility, I think of the old Wall Street quote used by traders: “Never catch a falling knife.” Quotes from traders are known for being blunt, graphic and a bit rude. No one can know where the bottom of this market is, except in retrospect.

When you have witnessed enough of them, you learn that “recession” is synonymous with“unpredictable.” There are always a few lucky souls who predict a recession and act on it. But like victims of the proverbial baseball bat, 99.99% of us never see it coming until it is too late.

A major reason for that unpredictability is the fact that each recession has a different origin. There are almost no lessons to be learned from scanning the horizon. The oil price shock and credit distortions of 1990-1991. The tech and accounting scandals of 2000. The housing and banking debacles from the Great Recession of 2008-2009. And now in 2020, an exogenous recession as a microscopic virus sweeps through the world.

A second defining characteristic of a recession is that we cannot know how long it will last. When people don’t go to work, don’t travel, don’t eat out and don’t go to stores, then we might be in a recession. When those activities will restart and when the economy will return to a semblance of normal is anyone’s guess. And guessing it will be.

For those of you who were considering a sale of your company before COVID-19 or are considering a strategy to sell on the other side of this economic shutdown, the recession may be guesswork, but what happens during it should not be. There are valid observations from past downturns that likely will be operative in this one.

Mergers and Acquisitions

Thousands of transactions occur year-end and year-out, boom or bust, expansion or recession. The M&A market never shuts down. Owners reach retirement age. Funds reach the end of their holding period. Sellers need capital and a larger partner in order to grow. Buyers need new product lines or services in order to compete in a new environment (think Cloud, telemedicine and online learning). There are a hundred reasons why deals happen - and they do.

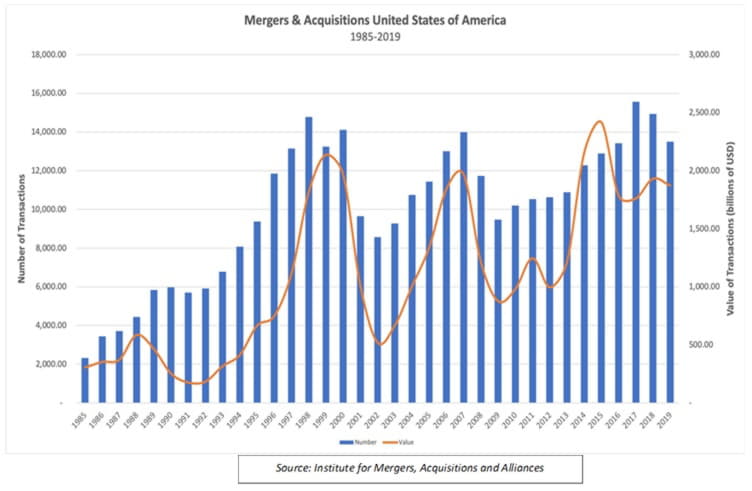

In the accompanying chart, 1990 was a record year for numbers of M&A transactions completed in the United States. In the recession year of 1991, the number of transactions dropped a mere 5% but the total value of those transactions dropped 30% from the year before. In the recession of 2001, the number of deals done dropped 31% from 14,114 to 9,652, but again the volume or total dollar of the transactions dropped even more at 48.6%. The same was true for the 2008-2009 Great Recession.In each case, there were plenty of transactions completed in a recession year, but the dollar volume dropped significantly.

The message is simple enough. The big headline deals that typically appear at the end of an economic expansion disappear or go on hold. (Xerox/HP, Mylan/Upjohn, Willis Towers Watson/Miller divestiture, Woodward/Hexcel.) Average deal size drops. But thousands upon thousands of small and middle market deals continue to get done.

Pricing

This is not to say that prices and multiples paid remain at the same level they were before the recession. The psychology of multiples, of what you will take as a seller or of what a buyer will pay, is complicated. For most of a company’s life, these two desires do not intersect.

Imagine that the economy is going gangbusters. Your business is growing its revenues at 15 percent a year, making $1 million in EBITDA this year. Along comes a buyer who offers you six times (6X) EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization or “cash flow”) or $6 million. In a no-growth scenario, this is effectively saying that someone will give you six years of profits up front. But you are growing rapidly, and you realize if you keep the business, you can bank cumulatively $8.7 million of profits in those six years. Selling now seems like a giveaway of $2.7 million to the buyer. So, you will not sell until the buyer comes back with at least an eight times (8X) multiple of EBITDA.

Now imagine this next scenario. We are coming out of a recession. Your 15% revenue growth has shrunk to zero. You are struggling to maintain your $1 million of cash flow. There is a lot of uncertainty in the market, and you cannot predict when the market for your goods and services will start growing again. Along comes a buyer who offers you five times (5X) your EBITDA. As explained, you are effectively getting five years of no-growth profit up front. You can forgo five more years of market, employee, product,and other risks.With this second lower offer, you can put that $5 million safely into U.S. Treasuries, sleep well at night, and maybe look for a second home in Florida. A year earlier, you rejected a 6X purchase price. Now, a 5X purchase price has a lot of merit.

Surf’s Up

There is a catch to this scenario. When multiples come down after a recession, sellers still have imprinted in their minds the pre-recession high multiples. There is often a lag time before sellers can adjust to the new pricing, the new risk/reward equation. Those who broker mergers and acquisitions (investment bankers) know that transactions often occur when both the buyer and the seller are equally unhappy.

The buyer pays a little more than it wants to, and the seller takes a little less than it expected. With some compromises and a re-imaging of the current market, both parties walk away only moderately pleased with the pricing. That is the nature of M&A. Deals will happen thousands of times over in the coming year. And many a seller will finally buy that home on the beach.

Doug Schmidt has been an investment banker for over 35 years, specializing in small and middle market merger & acquisition transactions. His previous firms include Drexel Burnham Lambert and Legg Mason Wood Walker before founding Chessiecap, Inc. in Maryland in 2004.